Okay, I admit it: I love Transformers. Always have, probably always will. So naturally, as a game designer, I’ve always wanted to see a really good Transformers game. Transformers is owned by Hasbro, which also owns Wizards of the Coast, so you would think at some point they would release a game worthy of the license, but to date, they just haven’t

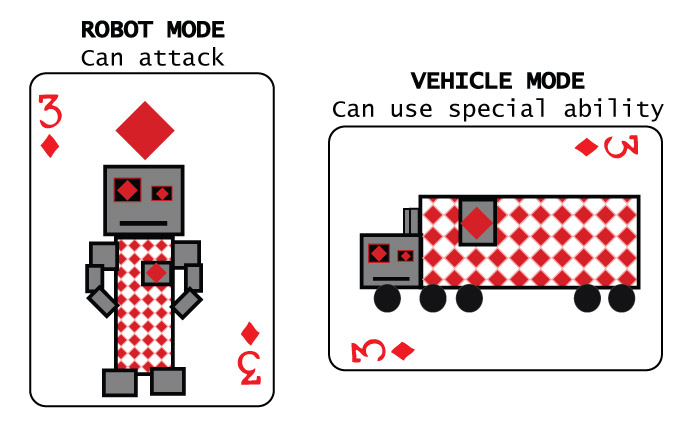

By the time Sam and I started working together, I’d toyed around with multiple half-baked ideas for a Transformers CCG, but the only mechanic I was really in love with was a simple one: Cards should transform, I decided, by turning sideways. Vertically, they would feel like robots, and horizontally, they’d feel like vehicles. It made perfect sense.

I had told Sam about this idea (which I was convinced was a lot more brilliant than it probably actually was) at some point, and sometime in the middle of our greatest stretch of game book design productivity, he said, “Hey, you know that idea you had for a Transformers game? I bet we could do it with playing cards.”

I was reluctant. Wasn’t this the idea I was going to sell to Wizards of the Coast someday to make all my robot-related cardboard dreams a reality? But I went along with it, and pretty soon, we were talking mechanics.

What You Can Do With a Playing Card

The most obvious issue we had right off the bat was how we could make a simple playing card feel like a robot with two distinct modes. My previous half-baked Transformer designs had been loaded with complexity, with special stats for each mode, so as to perfectly encapsulate all my favorite characters’ abilities. There was no way we could capture all that on a playing card… right?

Thankfully, Sam saw that we didn’t need that much complexity. We realized that all we really needed was a clear delineation between what a card could do in each mode, something that made which mode it was in relevant. We turned to our trusty tool: Suit abilities. Players, we had learned, could pretty easily internalize a different ability for each suit. We could limit those abilities to only functioning in one mode and increase the complexity of the play experience without really increasing the difficulty of learning the game.

Suit abilities made sense for vehicle mode, but what would robot mode have? Why, robot mode could attack, of course. Sam liked the idea of having two forms of attack–one closeup, and one long-range, with the long-range one dealing less damage. How would we delineate between the two? The most obvious binary on a playing card is between red and black, but if we’d done that, all Spades would essentially be the same card, as would all Hearts. Separating the even-values from odd-values lent more texture; now there would be 8 possible basic Morphatrons instead of 4.

Of course, that didn’t seem like quite enough variety, so we added the Special Forces. It just felt as though face cards should somehow be more fearsome than standard Morphatrons. We figured we were going to have to have special definitions for the face cards anyway (since they weren’t even or odd), so we might as well make them especially awesome, as befit their royal stature. Building up to them would also allow for some different strategies, and change the rhythm of some games.

Need for Speed

Our initial rules called for each player to take one action, with any number of bots in one zone attacking simultaneously. Many bots attacking simultaneously was such an embarrassingly bad idea that I don’t think we ever actually tested it, but we did try one action a turn. It was miserable.

Tactical games in which you get one action a turn tend to be really plodding affairs, in which any move forward is immediately punished. Since you have a limited ability to change things on your turn, staking out early positions proves all-important. That’s true for many games, and it was true for Morphatrons.

So we switched to two actions per turn. Now, games were moving much more fluidly. Being able to move and then attack was a real improvement. But we had one big problem: Bots weren’t morphing enough! This was a game about transfor–er, I mean morphing robots, but spending an entire action to change the orientation of one of your cards just proved too costly. So we added the Free Morph to the game. It proved perfect. You almost always wanted to morph at least one bot on your turn, and now you could justify it. Now bots were changing shape left and right, but not at such a fast clip that their orientation was trivial. It also made the move-two-spaces ability actually useful, which had not previously been the case.

You may notice that even with this change, the pace of Morphatrons is fairly measured. There are a few reasons for this. First, there are the flavor ones; it feels right for gigantic robots to rumble across battlefields–unless they’ve transformed into a sports car that is. But the pace is also integral to the game engine; it allows us to elegantly avoid an overt resource-based system of paying for bots. What the heck do I mean by that? Well, for the game to work, it has to be about robots fighting. For that to be the case, it has to matter when robots are destroyed, and that means those robots have to have some kind of value. To have value, they have to cost something. But in Morphatrons, they don’t appear to. You can just drop them right out of your hand. There’s no resource pool, no overt cost system. They’re just free.

But the truth is that the robots only appear free. In reality, they cost an action to play, and another action every time they move. They also cost a card, and it costs an action to draw a card. When a bot is destroyed, you’re actually losing a several-action investment, especially if it’s close to your opponent’s home zone. In effect, limiting what you can do on your turn turns the turn itself into the game’s fundamental resource. And you might notice that three of the four suit abilities grant you some form of action efficiency.

Indefensible

Maybe the thorniest issue in testing was making the Defense ability work. The idea was simple enough–it would make it take an extra shot to kill a bot. But that was when we were thinking about the unworkable “everybody shoots at once” plan. With individual range shots requiring an action, the entire damage system got more murky.

The first step was simple enough: Shooting with a ranged weapon had to inflict permanent damage, so that meant adding a chip to the card. Hence the creation of the critical damage chip.

But how would defense interact with it? We went through a number of unpleasant options before arriving at the current system. While the actual permutations we went through probably aren’t all that interesting, it’s worth asking: Why did we bother? Why were we so insistent that we needed this ability?

The answer is that in a plodding, tactical combat game like Morphatrons, players need ways to break stalemates. They need to feel they have ways to get a leg up on their opponents, or they’ll never advance, and the game won’t go anywhere. Defense represents an important piece of that puzzle. It really helps shape the battlefield, and create asymmetrical confrontations.

The system we wound up settling on isn’t perfect–it’s not exactly what I’d call “elegant”–but it does have some nice elements to it. It essentially makes the value of an attack action variable in an often interesting way. After all, if you deal a minor damage chip this turn, and next turn the defense bot morphs, that was a wasted action. But if you invest the effort into getting a critical damage chip on a bot, you know that bot’s big mechanical ass is yours, no matter how many buddies he has around him.

Morphatrons 2: Revenge of the Cardboard

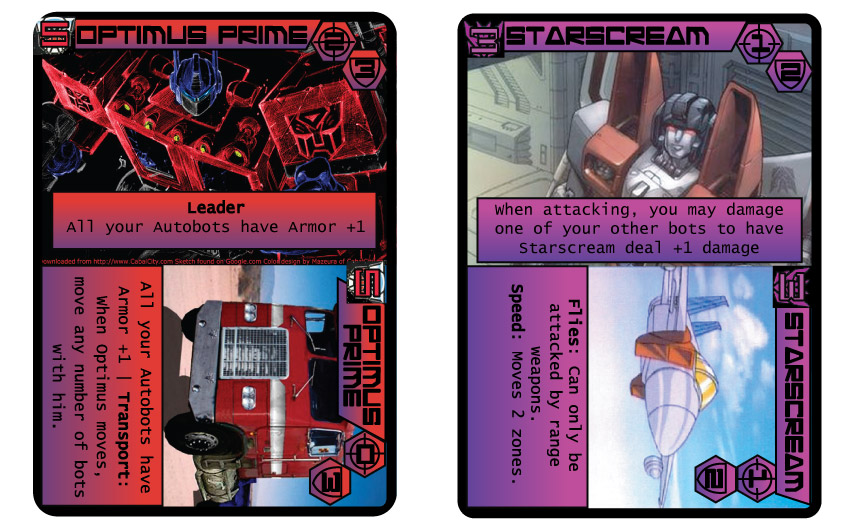

I know what you’re thinking. “Guys, I like this game,” you’re thinking, “But wouldn’t it be much better if you could just write all this stuff on the cards? That would be groovy. You should take this game home and make an honest, printed card game out of it.”

We’re glad you think that, even if only weirdos still use the word groovy. We think so too. That’s why we’ve got a Morphatrons game in the works! It’s still too early to tell the story of that design yet, or to say when you’ll see it, but it is something we’ve put a bunch of work into. Who knows, maybe we’ll sell it to Wizards of the Coast after all, and you’ll see something like this:

All images pilfered off the Internet in 2004. If you are the fan artist who made that Optimus Prime, I apologize for inflicting this terrible graphic design on your work.

The Transformers brand, which has nothing at all to do with Morphatrons, how dare you suggest such a thing, is the property of Hasbro, a very nice company that we’re sure is not litigious at all.